Delhi-based architect Revathi Kamath held a two-day mud and bamboo workshop close on the heels of the 11th edition of GRIHA Summit in Delhi where she introduced participants to the benefit of using earth architecture and techniques for a sustainable and integrated approach to development. The workshop also gave hands-on experience in sustainable architecture.

Delhi-based architect, Revathi Kamath of Kamath Design Studio, has always been a trendsetter amongst many of her ilk. Fascinated with form, design and structure while flipping architecture magazines during her growing up years, she went to study architecture and has since then always used it for social welfare. With her ingenious approach, she always looked into the sustainability aspect of buildings and fulfilled her social responsibility of being an architect even when there were no conversations around these topics and issues. The social aspects of architecture as espoused by Kamath and her husband, Vasant, way back in the Eighties were way ahead of their time. Through her "Evolving Home" concept, she designed a space for the community where the people, mostly coming from marginalised sections of the society, could work and live in the same space. The couple went on to successfully employ this design concept in building homes for the community of traditional performing artists and craftspersons called the Bhule Bisre Kalakar Sahkari Samiti in Shadipur, New Delhi, and then again with the weavers at Maheshwar in Madhya Pradesh. "For the unversed, it means that space grows as one's requirement grows. But some clients don't understand it, and are more in favour of modular structures," rues Kamath, sitting in her 45-year-old mud office structure in upmarket Green Park in the Capital. Her sensitive efforts in conceiving the concept have a set a benchmark in sustainable and socially responsible architecture. The award-winning architect has been associated with many landmark projects in her career spanning four decades but doesn't like to mention one that is her favourite. "My favourite is the next one. The one that's yet to come," says 64-year-old architect. It is also because she doesn't like looking back. "I am constantly moving forward. In the future, I see a lot of human beings living in harmony with nature. There will be a lot of positive and holistic search for our being. I see an ecological civilisation as our collective future," adds Kamath with optimism.

How were your formative years critical in shaping your design philosophy?

I was always interested in architecture, right from childhood. When I was only 6, I went on to supervise the building of a temple for myself. I built a little temple with snakes, bulls, and flowers, right opposite my mother's lily pond.

My grandfather, who was the then chief engineer of the Bhubaneshwar New Town, used to subscribe to an American magazine, Progressive Architecture, and many other architectural magazines because he was interested in architecture. He used to hero-worship an architect called Julius Vaz, and he wanted to speak with him on equal terms so he would avidly read everything on architecture that he could lay his hands upon. I lived with my grandparents and was constantly in touch with books on the subject that I chose to study and make a career later. I devoured all his books and the exposure early on in life kindled my desire and even before turned 10, I was familiar with names and structures. Flipping through the pages and gazing through the contemporary architectural works of Robert Venturi, Bruce Goof, Frederick J. Kiesler and Frank Lloyd Wright sparked my interest and deepened my understanding of different forms of architecture. I never liked the works of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe at that point of time. Maybe because unlike Wright whose work was celebratory, had so many rich textures and complex geometries, Rohe was a minimalist, and his work was way too sparse and spartan for me. I grew up liking the architectural designs of Frederik Kesner; his endless house was a curvilinear form which I found quite enchanting. He was mostly into set designs and models and didn't do too much architecture, but his forms interested me.

I had only two career choices — either take up architecture or become a nuclear scientist in which nuclear science came a low second. I realised that I would have had to study physics to become a nuclear scientist as my major subject, so I eventually went with my first choice and opted to study architecture. Even while pursuing architecture, I was clear what I wanted to do, and all of it happened because of my early initiation into the world of design, form, structure, etc.

During my college years at the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), my first sketch designs would be curvilinear and flowing, and wild. My teachers had to be tame it down drastically to make it a lot more practical. Once we went on a trip to Kerala. I saw Laurie Baker's work, and found it quite impressive, and decided that it was the direction I wanted to follow. We went all over the state and studied the vernacular architecture, reasons for why it was, the way it was. It caught my interest, and till date, I am still fascinated by the vernacular architecture.

The Anandgram Project is a big milestone in your career. What are some of your biggest learnings from the days of working with the underprivileged and marginalized communities?

I was deeply interested in not just architecture but also economic and social equity. That's another reason as to why I pursued my way of thinking. My first project after graduating from SPA that I worked upon was for the rehabilitation of community of traditional performing artists and craftspersons called the Bhule Bisre Kalakar Sahkari Samiti. They lived under the flyover in Shadipur in New Delhi. I worked with them for a year, and in a participatory way, I evolved a design for the community where they could work and live in the same space. It was a fulfilling experience. It informed me of a lot of aspects of architecture that I pursue until today.

In that one year, I got to understand their skills and compulsions and evolve a design with those people that gave my career a particular direction. We opted to make stabilized brick houses in that project. I have never left that. I have continued to evolve the technology of the mud architecture and stabilised earth construction ever since then. Gradually as time went by, and as I started to build, I started to understand ecology, and then my whole mind and being turned ecological. I started to assimilate the wisdom of traditions across the world. It became a search and thirst for knowledge relating to traditional ways of building and living. And it was holistic. I became eco-friendly towards my kind of work. I was interested in not just buildings, but clothes, food, health, agriculture, plants, and everything. I don't even have to justify it today because the whole world is moving in that direction. I started off a little early is all that I can say.

Have you been influenced by vernacular architecture from across the world?

Yes, of course. I have been profoundly impressed and also influenced by the adobe architecture of Mexico, Egyptian architecture, and French architecture. I remember meeting a Swiss architect who taught me how to make tiles were made with thatch and mud. I tried it out as well, but did not succeed. I have read a lot about earth architecture in China and bamboo architecture in the far-east. But the skills of bamboo artisans in Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, etc. are of a very high order. We don't have such expertise, except in the North East where there are a lot of skilled bamboo artisans. It has to be the whole culture to be built. The thrust is different. I don't believe in transposing my thoughts, but I want the architecture to come from people who live in those areas. I evolved my architecture so that people can adapt to the designs and build a structure.

What reforms can be brought about in the current architectural education system to promote social architecture?

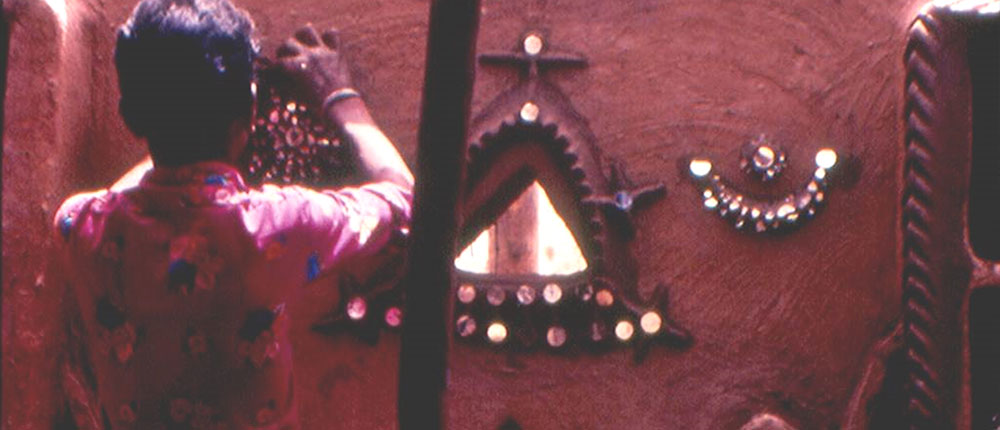

It is important. Architecture education neither sees nor assumes any social responsibility. It sees itself as a technical system that teaches technical and professional competence in these students of architecture. And that's all. There are no conversations around the social aspects of architecture. Like when I started, and spoke of the poor, housing and low-cost houses, I was always discouraged. In the early eighties, there were not many people who were even thinking on those lines. When I was working on this project, people were curious. They would make snide comments and often call my labour of love, not architecture but social service. Indeed there were no real efforts to educate one on the social responsibility of architects. Then, everybody was into commercial and monumental buildings. My experiences of working with the community shaped and formed me. It made me understand the complexity of making space. It gave me a better perspective of understanding community and architecture. It made me understand the simplest of materials, and skill and decoration. These aspects stayed with me. I got the self-confidence to pursue it. I still carry it with me.

What are the qualities that you look for in an architect?

I look for someone who is conscious of energy consumption, caring about aesthetics and beauty, and someone who is willing to work hard and not hung up on technology, uses technology and doesn't let technology rule his or her mind.

What measures can be taken to make mud a viable building material in modern construction?

My whole effort is to make mud a viable material. The embodied energy of mud is so low, it is the lowest. Mud is the most recyclable and sustainable material on this planet; it only uses small amounts of mechanical energy and huge amounts of human energy. It sustains human beings. Human input adds value to the material. And not just me, there are people in the US are talking about mud, and cutting-edge research is on to make it a viable material for building. It is an energy-conscious material. Mud has some qualities and it must be recognised as such. It should be looked as the go-to material as and when possible to conserve our environment. We must not reject mud as it is considered backward or Luddite. But accept and adopt it.

I don't use mud in all my projects. I don't push for it. People come themselves asking for it.

Is 'vernacular' more sustainable? What are some of the biggest advantages of incorporating traditional learnings in building design?

Vernacular is indeed more sustainable. Vernacular is something that belongs to the people and place. Vernacular has to do with the language, and even architecture has a language. It is natural. There are influences from all over, and as a result vernacular is getting diluted and slowly dying. But objects that you would surround yourself need to be of the place. Till that consciousness dawns upon people and people become mindful, it is tough for vernacular to survive, and sustain itself. It has adopted and evolved as per the climate and resources of a particular place and its people. It has adapted and evolved to become the best fit.

Whose work has inspired you over the years?

I find the works of Shigoru Bhan in Japan and Colombian architect Simone Velez quite inspiring.

Can behavioural changes impact our resource consumption? What would be your message to the millennials in this regard?

The millennials are, no doubt a conscious lot. And they are opting for sustainable options far more than the previous generation, and this behaviour bodes well for them in particular and the environment in particular. But there are only a few of them as of now. The mainstream is being marginalised. It is not just here in India but across the world. People are changing, and that's quite a hopeful situation. When we started, we were like lone warriors, but today a lot more people are conscious, and so there are many movements across the world. The millennials are all for all things sustainable like living in the natural environment, appreciating plant life, eating organic stuff, etc. The idea is slowly percolating. But it will take some time to become more popular among the masses, but the process has started.

Quotes

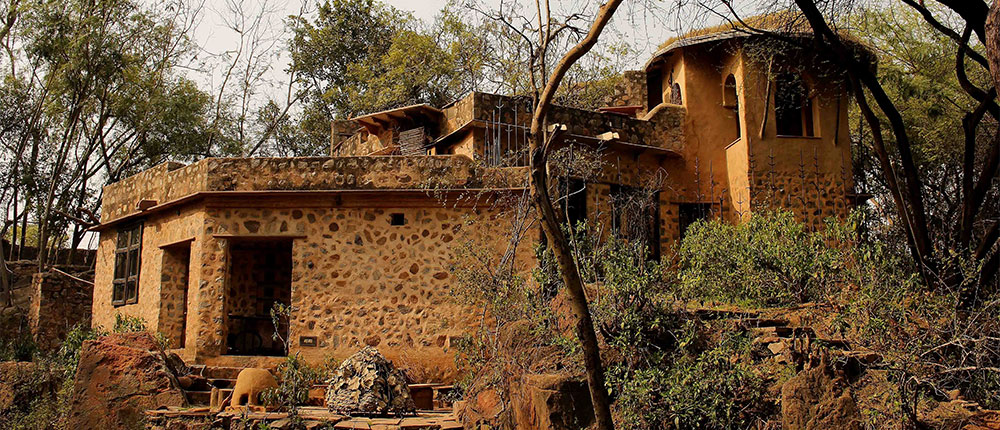

"Kamath House and Gnostic Centre are two of my favourite projects by Revathi Kamath. Reflective of Kamath's immense reverence for natural ecological processes, the projects highlight why it's important for architects and designers to be cognizant of such processes while studying a site and building on it. In addition, both buildings illustrate a level of material innovation and ingenuity in structural design that is staggering. While working with fluid forms has become a trend in today's world, most practices achieve this with the help of digital tools and construction mechanisms. Shaping such complex ideas with principles and fundamentals that are centuries-old – local materials, skill-sets and building techniques – is incredibly inspiring. And especially so for a practice like 10by10 studio that is as committed to giving back to nature and local economies as it is to exploring modern technology to find smarter solutions for our collective future."

Nebin Asharaf, Conceptualizer Principal | 10by10 Studio

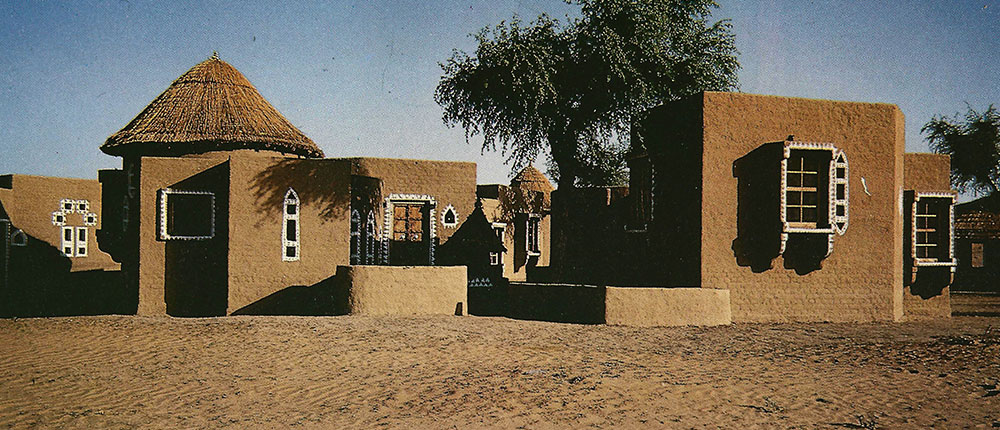

"The workshop — Introduction to Mud and Bamboo Architecture — held at TERI Gram, Gwal Pahari, on November 23 and 24, 2019, introduced me to the properties, basic testing techniques and limitations of the materials followed by a detailed explanation by Ar. Revathi Kamath. She gave a rundown of her projects over the years, including Anand Gram; Desert Resort at Mandwa Rajasthan having cottages and craft area; Nandita Jain's Mud House where mud brick arches of 6'x10' were used; Akshay Pratisthan School in Delhi for physically challenged kids with low-height interior mud walls for well-connected spaces, with ample natural light and ventilation; and Kamath House in Haryana where mud bricks were made at the site and the ditch was later converted to water body. It was amazing to learn about their construction processes and different materials used for these structures. These designs were built using local participation and materials were used with innovation or intertwined with other building construction materials. Vernacular technique is a better option for any organic or irregular form. It has better structural strength, is earthquake resistant and merges well with the nature. I am inspired to use vernacular material because it is sustainable and environmental friendly. As an academician, I will ensure that my students are aware of such materials and develop sensitivity towards our environment."

Ar Ruma Singh, Associate Professor, SMAID, New Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat