The article explores the various dimensions that inform a just transition and the complexities involved in moving away from coal through a case study of Betul which has seen a spate of coal mine closures, due to mineral exhaustion

As we push ahead to reach sustainability goals in this 'decade of action', efforts to tackle climate change have reflected how daunting the task at hand is. For the world to meet the target of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C as laid down by the Paris Agreement, it is critical to shift our economies and their drivers to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Coal has employed a large section of people for decades by developing their skill sets to cater to the needs of the industry. Moreover, coal mines have also led to the emergence of several townships around them. However, as the world transitions away from coal, a large section of people dependent on its extraction may suddenly find themselves out of jobs, and the once prosperous townships could turn into ghost towns.

A case study by TERI, on the impact of the closure of coal mines in Betul, a district in Madhya Pradesh with a mining history of 150 years, sheds light on these issues and the growing need to recognize 'just transition' when moving away from coal.

Four of the 10 coal mines in Betul closed down in quick succession due to mineral exhaustion. The last of the four closed in 2013 and two more mines are slated for closure in 2021.

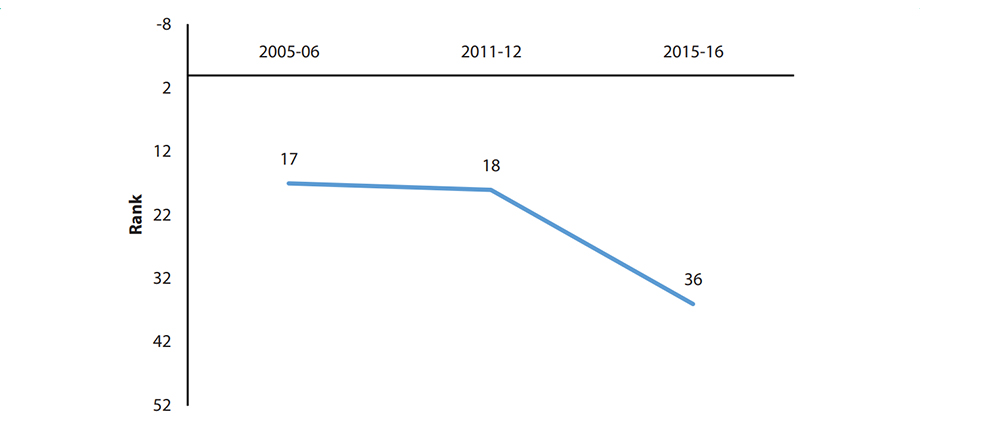

The study titled, 'Mapping the Impact of Coal Mines and their Closures: A case of Betul' observed that there was a simultaneous fall in the secondary sector (manufacturing, electricity, and construction), and tertiary sector (trade, repair, hotels and restaurants, and financials) of the district's economy as the mines closed. This centrality of coal mining to Betul's economy became even more evident as the per capita income based ranking of the district fell from 18th in 2011-12 to 36th in 2015-16, coinciding with the mine closure.

Socio-economic impacts of mine closures

In a podcast with the Climate Investment Fund titled 'Just Transitions Podcast: India's Path Forward,' Dr Ajay Mathur, Director General, International Solar Alliance, notes that the communities within the mining regions are socially, environmentally and economically 'broken'.[2]

As the mines run dry so does the opportunity to work, not just within but outside the mines as well. As migration out of the region increases, the township begins to decline, and employment opportunities keep thinning, which eventually leads to the community falling apart.

The study also added that by 2030, 46% of the workforce strength of 2019, will retire. In Betul's case, the declining regular workforce has been replaced with informal, contract workers. While this helped meet the challenge of a reduced workforce, it gradually increased inequality and marginalization in the labour market. The disparity in entitlements and working conditions between the regular and the informal, contract workforce reduced their purchasing power, consequently bringing a reduction in the demand for goods and services in the local economy.

Increasing reports of cases of stress and anxiety in Betul, as pointed out by union representatives and medical teams in the coal field, further brought to the fore the social implications of an unplanned transition.

Dr. Tejaswi S. Naik, former District Magistrate of Betul, said in a discussion on just transition in India at the World Sustainable Development Summit 2021 that, "the winding down of the coal industry leads to a sharp rise in crime." Betul saw something similar with the closing of the mines as drying opportunities around coal manifested themselves in the form of increase in the reported crime. According to the report, theft of cables and pipes from abandoned mines, theft in residential quarters of the industry, and theft of diesel from trucks has become increasingly common. In the larger context of a just transition of the energy sector, this indicates the fragility of the mining community and of the region.

The criticality of the study comes from the possibility of extrapolating the findings from Betul to a larger, global energy transition context. It is true that the benefits of transitioning to a low-carbon economy as soon as possible far outweigh the costs of continuing with the business-as-usual model. But if the transition is not 'just', it might leave entire workforces and communities in the lurch. Climate action finds its foundation in sustainability and inclusivity, underlining the need to bring everyone together to work for a common goal. Excluding anyone in this effort could very well push us further away from any form of progress that has been made against climate change.

Loss of traditional forms of livelihood

The closure of mines in Betul, where coal seemed to be infinite to the workers and local communities, led to a range of complex issues. Agriculture that formed the traditional means of livelihood for the district saw a significant decline in land holdings possessed by cultivators and was accompanied by an overwhelming increase in the proportion of agricultural labourers. Coal dust from mining greatly hampered the agricultural produce. Depleting ground water and shrinking availability of fodder has made agriculture even less remunerative than before. Moreover, with high outmigration rates finding labour during the cropping season has also become quite difficult. As the mines closed, and the township declined the market for agricultural produce shrunk even more.

Political Impact

Since the region has been historically associated with mining, a low carbon future pathway, does not find ready acceptance. This has led to the emergence of local forums in the region such as 'Udyog Bachao Nagar Bachao' which have been demanding the opening of new mines, setting new units of power plants to bring back the decaying town to life. With limited local economic opportunities, the traders and businesses in the coal area feel threatened by those coming from outside the district to trade.

Moving away from the carbon lock-in

The transitioning of carbon intensive industries to greener solutions needs a sharper focus on the social consequences entailed by such a shift as has been enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals. While a potential transition from carbon intensive to low-carbon industries seem to have a number of challenges, TERI's study also presents a way forward. Recognising the importance of climate action and the urgency with which industry transition is necessary, the study suggests a tailor-made approach for Betul district that specifically focusses on enhancing rural incomes and livelihood opportunities to reduce vulnerabilities. A shift to a sustainable economy while keeping the idea of just transition in mind requires strengthening agriculture, improving educational outcomes, and enhancing labour market with newer skills and newer opportunities.

With public sector undertakings planning to diversify and tap into renewables in the future, the study suggests that these organisations work in close partnership with training institutions in the private sector to identify skills of the future, particularly those in renewables and energy efficiency. Promoting micro, small and medium enterprises by ramping up of opportunities in green products and services and in green entrepreneurship is another suggestion to promote and scale up innovation and employment generation.

The case study of Betul offers a granular insight into the complexity that surrounds energy transition. It outlines the challenges that a community and region historically involved in coal mining face when that lifeline is cut. But more importantly it explores a way forward for these 'broken' regions and communities, but not without highlighting the need for a social dialogue listening to what people have to say. Betul is indicative of the situation in other mining districts in the country. The study takes a deep dive and understands the consequences of non-preparedness for mine closure. In the process, however, it also reveals the fragility and finitude of fossil fuels and the uncertain future that awaits a majority of the mining districts of the country unless proper actions are taken and just transition given its due importance.

Footnotes:

[1] Estimates of District Domestic Product 2011–12 - 2016–17, Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Madhya Pradesh accessed from des.mp.gov.in

[2] https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/news/just-transitions-podcast-india%E2%80%99s-path-forward