The Director General, TERI, gave a public address on 'Clean environment as a Human Right: Exploring synergies between the environment, SDGs, and human rights' at the Silver Jubilee Lecture of the NHRC, in New Delhi on 10th September

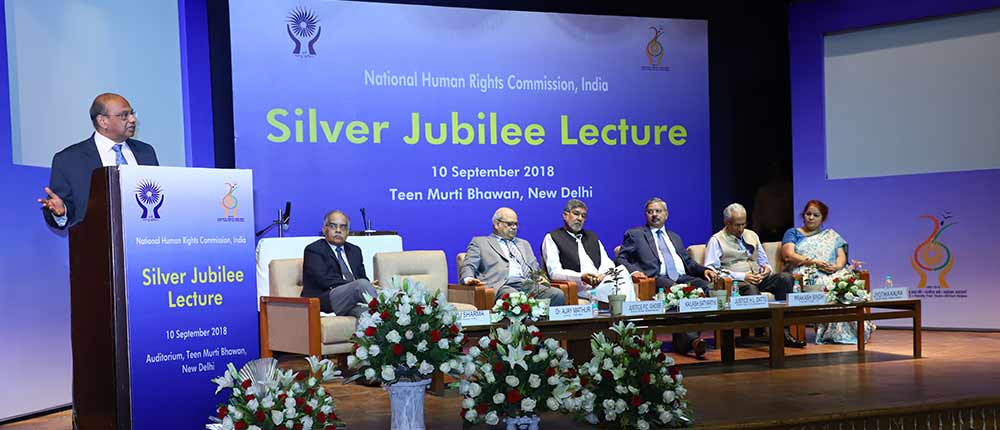

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), India, held its silver jubilee lecture on 10th September 2018 in New Delhi. Kailash Satyarthi, Noble Peace Laureate, attended the event as chief guest and Dr Ajay Mathur, Director General, TERI, and Prakash Singh, former Director General of Police, Uttar Pradesh were the guests of honour.

At the event, presided over by Justice HL Dattu, chairperson, NHRC, all three guests spoke about various aspect of human rights. While Mr Satyarthi talked about this fight for child rights, Mr Singh raised the point about consideration of the human rights of police personnel. Dr Mathur spoke about 'Clean environment as a Human Right: Exploring synergies between the environment, SDGs, and human rights' and urged the NHRC to initiate a dialogue on the issue of the right to a clean environment as a human right. The following is his full address -

"Justice Mr Dattu, members, Secretary General and officers of the National Human Rights Commission, ladies and gentlemen:

I congratulate the National Human Rights Commission on its Silver Jubilee, and even more importantly for institutionalising a process for the protection and promotion of human rights, including through the complaints that it receives and through the suo-moto recognition of potential human rights violations. The over 10,000 cases that the NHRC has disposed, and nearly 20,000 cases are under consideration speak of the here-and-now importance and relevance of the NHRC in ensuring that we continue to cherish and enable rights relating to life, liberty, equality, and the dignity of the individual as guaranteed by the Constitution or embodied in international covenants.

The National Human Rights Commission, as well as similar commissions across the world, reflect the reality that these rights, relating to life, liberty, equality, and the dignity of the individual, are often not met or inadequately met. The varying sets of issues taken up by this Commission, and by the Commissions in other countries, also reflect the reality that the challenges to these rights are different from country to country, and also from time to time. In other words, what was not a human rights issue yesterday may become one today, as is the case with homosexuality which was decriminalised by the Supreme Court last week based on rights to equality and dignity. In other words, now - as opposed to just five years ago when the Supreme Court had upheld Section 377 which criminalised homosexuality - protection to homosexuality is seen within the context of potential human rights. In other words, new human rights emerge over time, and different societies and classes of people within societies, have different sets of priorities about their most valued set of human rights.

I would suggest that a clean environment is now emerging as a human right in India. It was not an issue 100 years ago because at that time, we produced very little waste, and that waste was easily absorbed by the environment around us. However, as we have developed, as we produce and consume more, and as our population density has increased, pollution now lives cheek to jowl with us: these include landfills that are falling onto neighbouring buildings; particles and NOx that choke us; and wastewater which sloshes over our shoes every time we cross roads in front of our homes or offices or factories. I would like to briefly outline the contours of this transition.

Globally, the discussion on the inter-linkages and synergies between human rights and the environment has centred around three major questions: firstly, whether environmental protection is required to meet basic human rights; secondly, whether human rights can contribute towards environmental protection; and thirdly, whether environmental rights are basic human rights.

This complementarity between the two was first recognised in a Resolution of the UN General Assembly in 1968. The Resolution expressed a concern about the effect of the deterioration of the environment on the ‘condition of man, his physical, mental, and social well-being, his dignity, and his enjoyment of basic human rights, in developing as well as developed countries.’ In other words, there is both an anthropocentric urgency as well as an eco-centric urgency.

In the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment adopted at the UN Conference of the Human Environment in 1972 both approaches are evident. You will recall the influential impact of Stockholm meeting; it was at this meeting that Mrs Gandhi had linked a clean environment to human dignity; stating that, "poverty is the worst pollution".

In 2003, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (now, the UN Human Rights Council) highlighted these inter-linkages more clearly when it stated that respect for human rights is essential to achieving sustainable development, that environmental damage can have a negative impact on the enjoyment of some human rights, and pointed out that states should be cognizant of the negative effect of environmental degradation on disadvantages sections of societies in particular.

Since then, the Sustainable Development Goals, adopted as a part of the 2030 Agenda for Development have taken this discussion forward in some ways, which I will discuss later.

In the Indian Constitution, improving public health is included as a Directive Principle. The Parliament passed the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 as an omnibus legislation empowering the Central government to take measures and protect and improve the quality of environment and to control and abate the environmental pollution. It also created the National Green Tribunal, under the National Green Tribunal Act 2010, for the more effective enforcement of legal rights connected to the environment.

I also note that during the past decade or so, a number of regulations issued under the Environmental (Protection) Act have specified bench marks for, inter alia, landfills, air quality, plastics and battery wastes, etc.

However, In India, the inter-linkages between the environment and human rights have largely been understood through judicial interpretations of constitutional provisions. For example, in 1985 in Rural Litigation and Entitlement Kendra vs. State of Uttar Pradesh, the Supreme Court ordered the closure of certain limestone quarries followed by land reclamation, afforestation and soil conservation in those areas, pointing out that while the closure of these mines would cause losses to owners and employees, this was a necessity for "protecting and safeguarding the right of the people to live in healthy environment with minimal disturbance of ecological balance and without avoidable hazard to them and to their cattle, homes and agricultural land and undue affectation of air, water and environment."

In the landmark case of MC Mehta vs Union of India, in 1987, the Supreme Court ordered certain polluting industries along the Ganga river in Kanpur to establish primary and secondary effluent treatment plants. While discussing the financial implications of this order, the Court stated that the financial capacity of these industries to set up treatment plants was irrelevant in this context, as "a tannery which cannot set up a primary treatment plant cannot be permitted to continue to be in existence for the adverse effect on the public at large which is likely to ensue by the discharging of the trade effluents from the tannery to the river Ganga would be immense and it will outweigh any inconvenience that may be caused to the management and the labour employed by it on account of its closure."

These cases moved environmental rights from being an economic issue to a social issue.

It was in Subhash Kumar vs. State of Bihar, in 1991, that the Supreme Court directly linked environmental protection with the right to life guaranteed under Article 21. While delivering a judgment in response to a public interest litigation (PIL) filed against industries, which the petitioner alleged were polluting the Bokaro river, the Court held that the right to life, guaranteed under Article 21, also includes the right to pollution-free air and water.

When I put together the jurisprudence and the legislation, including the specifics of the regulatory bench marks, I am persuaded that the right to a clean environment has emerged as a new human right in our country. This has obvious implications for future jurisprudence, but also for the National Human Rights Commission in terms of an expanded scope which includes the need to protect individuals and communities from pollution.

It is worth spending some time on thinking what are other new rights that may emerge, similar to the emergence of the right to a clean environment? To me, the Sustainable Development Goals, of which the goal for a clean environment is one, could provide an answer. This is largely because of the manner in which the SDGs are crafted. The preamble of the UN Resolution which adopts the SDGs clearly states that the SDGs "seek to realise the human rights of all", and pledges to leave no one behind. Its focus on ensuring that "all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity and equality and in a healthy environment" is also reflective of the manner in which the human rights approach underpins the SDGs.

Consequently in the SDGs, there is no specific goal on the achievement of human rights; the approach is that each of the SDGs leads to outcomes which are inclusive and equitable and is implemented in a transparent, participatory and accountable manner. Human rights become central to each of the SDGs.

At this juncture, then, it becomes important to highlight the inter-linkages and synergies between SDGs and human rights, and to stress that progress on both can be accelerated if implemented in a mutually reinforcing manner. It seems to me that with the framing of the Sustainable Development Goals as a means to meet human rights, we will see more of these goals, apart from the SDG relating to a clean environment, enter into the lexicon of human rights.

It seems to me that we, as a society, are ill-equipped to deal with these new and emerging human rights. Apart from the limited capacity and capability of these issues, there is also a lack of consensus on the approaches that are needed to ensure that these human rights are preserved, protected and promoted. For example, if my neighbour throws his waste in front of my door, is that a violation of my rights related to life, liberty, equality, or my dignity? We will probably have divided opinion on this. On the other hand, consider the continued dumping of wastes in large landfills. It is probably a clearer case of the violation of the human rights of the thousands of people who live around the landfill. I paint these two pictures at opposite ends of a spectrum to highlight that we do not know where in between these two extremes the violation of human rights starts.

A second issue relates to the availability of credible information relating to the impact of pollution on people. I want to separate this from the issue of the violation of benchmarks, which is a legal issue that will be settled by the courts. However, I believe that there is a lack of understanding of how an objection will be dealt with which claims, for example, that by the Gazipur landfill site, or the air quality of the National Capital Region, endanger the life and dignity of the people impacted by the pollution. I believe that there is an immediate need to develop consensus on a corpus of knowledge about the actions through which the lack of a clean environment hampers human rights.

I respectfully urge the National Human Rights Commission to initiate a dialogue on the issue of the right to a clean environment as a human right so as to help build a common understanding on both the substance of that right, as well as the limits of that right."