The Land Resource Inventory developed under Sujala-3, a watershed management scheme in Karnataka, empowers farmers with site-specific information to boost farm incomes

Karnataka has the second highest percentage (79%) of drought-prone arid land among all major states in India. In addition, Karnataka also has the lowest, second only to Rajasthan, availability of groundwater in post-monsoon months.

The state’s net agricultural land is 10.79 million hectares (MH). Out of this cultivated land, nearly 75% is rainfed, depending on inconsistent rainfall during the southwest monsoon. Given that 60% of the state population is sustained by agriculture-related livelihood, the focus on watershed development activities in Karnataka is essential.

Started in 2013-14, Karnataka Watershed Development Project-II, also locally known as SUJALA-3, is being implemented by Watershed Development Department (WDD) and Department of Horticulture (DoH), Government of Karnataka. Supported by the World Bank, this programme aims to demonstrate effective watershed management through science-based approaches, and strengthen institutions and capacities. It is being carried out in 11 districts: Bidar, Chamarajanagar, Chikmagalur, Davangere, Gadag, Kalaburgi, Koppal, Raichur, Tumkur, Vijayapura, and Yadagiri.

“The project is encouraging small and marginal farmers to adopt new technologies and conserve natural resources in a more scientific manner which helps them in stabilising their livelihood for the long term,” says Prabhash Chandra Ray, IFS, Commissioner, Watershed Development Department.

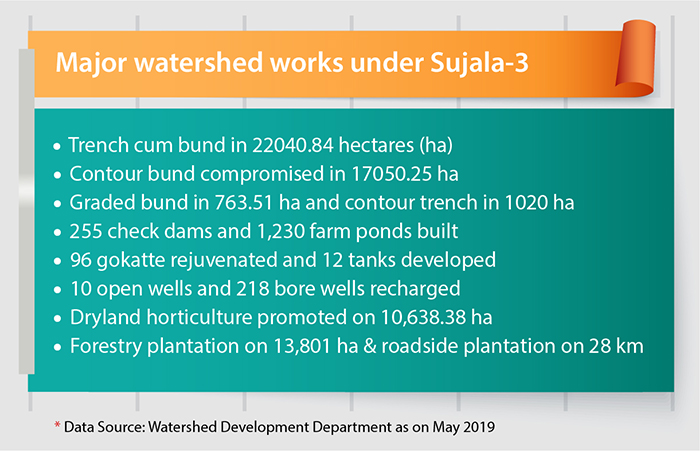

So far, the programme has created a large number of soil and water conservation structures including farm ponds, check dams, Nala bunds, gokattas, etc, apart from promoting dryland horticulture, forestry plantations, livestock to enhance livelihoods, skill trainings, income generation activities, etc.

Dr A. Natarajan, NRM Consultant on Sujala-III Project (WDD) stresses that the watershed programme under Sujala-3 has been planned carefully by integrating scientific knowledge. He states, “Not only in Karnataka but in India, the distribution of planning inputs by research institutes has been lacking. Most of the watershed programmes, which are about five decades old, have not been able to address this at the grassroots level. Only a few farmers are familiar with the nature of their land but there are no inputs available to them about the amount of rainfall and type of soil or landforms. This project is one-of-its-kind for providing tailor-made or customized information about soil attributes to farmers.”

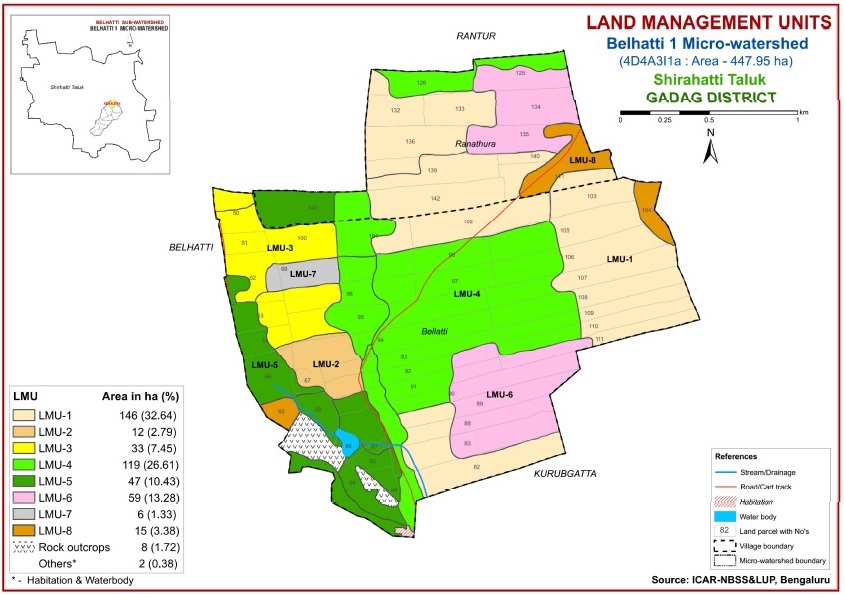

Under Sujala-3, crucial information has been collated by the National Bureau of Soil Survey and Land Use Planning (NBSSLUP) and University of Agricultural Sciences (both of which are LRI partners), who have carried out a detailed soil profile at parcel level i.e. farmer field level. After studying different soil conditions and climatic parameters, the project team developed the Land Resource Inventory (LRI) atlas for each micro watershed or Land Management Units. As of now, 85 LRI atlases have been developed by the LRI Partners for 85 micro watersheds spanning an area of 46,640.8 hectares in the nine saturation districts. In each district, the sub watershed area taken up for saturation treatment is about 5,000 hectares.

Farming communities get the lay of their land with LRI

Chandrappa Thaavareppa Nayak, of Nabhapur village in Gadag district, owns 12.5 acres of land. He remarks, “I used to grow only field crops such as maize, cotton, and grams. My land has a steep slope so the top fertile soil used to get washed away with rainwater.”

SUJALA-3 team built a large check dam adjacent to his land and farm pond on his land in 2017-18 to check the water flow and enable percolation. He declares, “Now, my crop yield from maize alone has grown by two quintals. And as per the information in LRI card, I have good knowledge about soil health and suitable crops for my land. I have also cultivated horticultural crops such as mango and lemon.”

Chandrappa is one of the several farmers in Karnataka who now have a better understanding of the crop potential of their land, thanks to detailed information such as soil types, climate, water, vegetation, etc. provided by LRI.

Dr Natrajan adds, “The LRI of each micro watershed sums up comprehensive site-specific cadastral level information in the local language. Farmers can find data as per their land’s soil texture, moisture availability, about what kind of crop is suitable, what will be the soil moisture availability for a particular period/season, what is the type of nutrient which can work for a crop, which scientific way would increase crop yield, etc. This atlas basically indicates the potential and limitations, through a series of thematic maps, of each Land Management Units (LMU) for farm level planning for all stakeholders.”

In addition to these atlases, SUJALA-3 team is developing a digital platform and a mobile application for farmers to easily find information about crop, soil, etc. “Once the information is uploaded on the portal, anybody can access this information. It is particularly useful for policy makers to formulate relevant schemes,” comments Dr Rajendra Hegde, Director of NBSSLUP.

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) took up the Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning and Documentation (MELD) of Sujala-III scheme in July 2017. Dr Lasya Gopal, Principal Investigator of the project, highlights, “For sustainable improvements in productivity and livelihoods, the LRI recommendations are shared with beneficiaries in all watersheds through training programmes at the village level.”

“Sujala-III scheme has given a new topic of research to students, developed a skilled pool of human resource and several of our students have also gained employment,” explains Dr P. L. Patil, Professor of Soil Sciences, UAS, Dharwad, one of the LRI partner universities.

Mallayya C. Koravanavar is the Assistant Director of Agriculture in Gadag District where Sujala-3 project covers 2,242 (72%) hectares of arable land. He explains, “Our district primarily falls under a hilly region and the ground is gravelled. In low-lying downstream areas, some bore wells and farm ponds filled to the brim which indicates the level of soil and water conservation that has been achieved. Also, the perception of farmers toward LRI has sensitised them to land capability.”

As Sujala-III watershed programme draws closer to the end of implementation, the sampled study/data show that there is considerable awareness about the suitability of land for various crops, thus enabling the farmers to obtain better yield and income gradually.

The state, through innovative ventures like SUJALA-3, has paved a way for increased crop yield and scientific management of watersheds. This momentum of positive changes has to be sustained until the dissemination and adoption of LRI, among all stakeholders, becomes more widespread and common in India.

Dr Natarajan concludes on an optimistic note, “The information we gathered for LRI is at least good for up to 25 years and not for just one season. With a few adaptations in approach, this kind of (SUJALA-3) programme can be put into practice in the Indian farming community.”